Glaucoma management is a lifelong endeavor that requires consistent monitoring, timely intervention, and patient adherence. Given the chronic nature of the disease and the increasing patient demand on stressed health care systems, collaborative care models have become essential. Among these, comanagement of glaucoma involving optometrists and ophthalmologists has emerged as a highly effective approach, blending the accessibility and clinical management skills of optometrists with the surgical expertise and advanced interventions offered by ophthalmologists.1-3 When thoughtfully structured, comanagement can enhance patient outcomes, streamline care delivery, and foster professional satisfaction for both providers.

Figure 1. When gonioscopic examination of a 63-year-old patient with glaucoma revealed a narrowed angle, the patient was referred to a glaucoma surgeon for evaluation.

Defining the Optometrist’s Role

Optometrists often serve as the gateway to glaucoma diagnosis, encountering patients during routine examinations or monitoring individuals already at risk. Their role in comanagement extends from early disease detection through to long-term glaucoma care.4 By using diagnostic tools such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), gonioscopy, and automated perimetry, optometrists can detect early glaucomatous conversion and initiate appropriate therapy. They are also vital in educating patients about the disease, emphasizing the importance of adherence to medication regimens, and conducting appropriate follow-up visits to monitor intraocular pressure, along with structural and functional stability.

For patients with stable disease who show consistent findings over time and demonstrate good control with medical or laser therapy, optometrists provide ongoing care and adjust medical regimens when necessary.

Defining the Ophthalmologist’s Role

Ophthalmologists bring critical surgical expertise and management of advanced or rapidly progressing disease to the comanagement model. They are pivotal in evaluating complex cases, confirming diagnoses when presentations are atypical, and determining when escalation of care is necessary.5 Their role becomes especially prominent when laser procedures or incisional surgeries are needed to control intraocular pressure.

In addition to providing interventions such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT),6 YAG peripheral iridotomy (PI), minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) combined with cataract extraction, excisional goniotomy with instruments like the Kahook Dual Blade (KDB),7 or advanced procedure like trabeculectomies, ophthalmologists help stabilize disease progression. They often re-engage directly with patients during periods of instability.

Identifying Clinical Scenarios Appropriate for Comanagement

The success of comanagement hinges on recognizing whether clinical situations are appropriate for optometric-directed care, shared care, or ophthalmologic-directed care. This may depend on the comfort levels of each optometrist and ophthalmologist.

Stable glaucoma is well suited for optometric-led follow-up.4 In contrast, unstable glaucoma characterized by progressive optic nerve changes, worsening visual fields, or consistently elevated intraocular pressures despite maximum therapy may necessitate a surgical intervention from the ophthalmologist.

Postoperative care after SLT, YAG PI, MIGS, or KDB is another area where optometrists can provide valuable and efficient follow-up, checking for pressure spikes, inflammation, wound healing, and medication management, while keeping the ophthalmologist informed of any concerning developments. Timely re-referral in the event of surgical complications or unsatisfactory outcomes is critical to maintaining patient safety and trust. Additionally, any surgical complications should be communicated promptly to the optometrist.

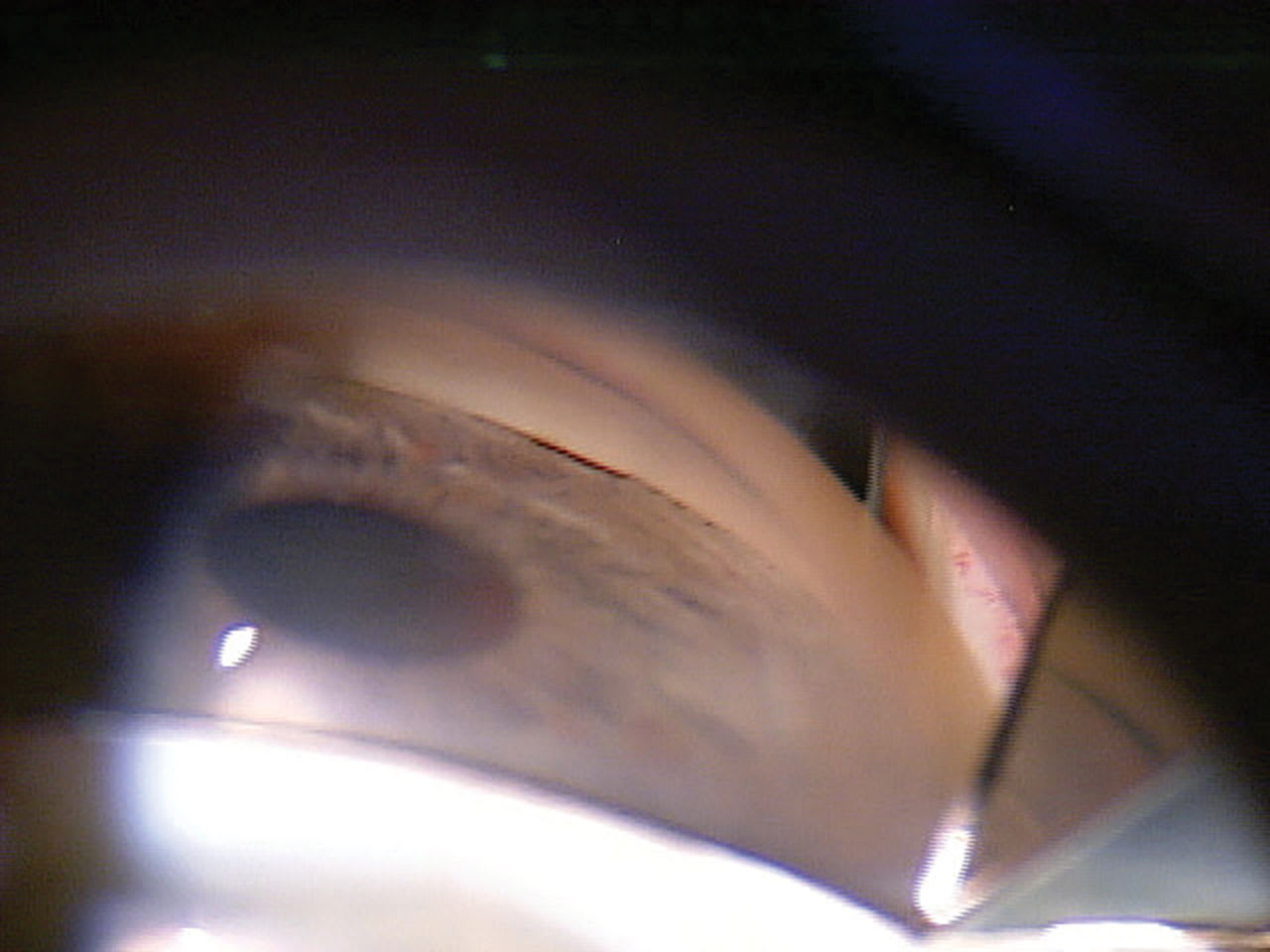

Figure 2. Angle-to-angle anterior-segment optical coherence tomography imaging shows an open angle. Goniotomy with Kahook Dual Blade created an opening to Schlemm’s canal.

Case

A 63-year-old White male presented to MC for a glaucoma consult. The patient was on 0.2% brimonidine and 0.5% timolol qAM, both OU for several years. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/25 OS with an afferent pupillary defect OD. His corneal compensation intraocular pressures were 23.7 mmHg OD and 21.8 mmHg OS. His corneal hysteresis was reduced to 7.3 and 7.8, and his corneal thickness was also reduced at 523 µm and 530 µm, respectively. OCTs and visual fields showed severe glaucoma OU. Gonioscopy showed iridotrabecular contact in all 4 quadrants (Figure 1). He had visually significant cataracts.

MC diagnosed the patient with chronic angle closure glaucoma OU and cataracts and discussed treatment options including LPI, cataract surgery, and the possibility of MIGS if the angle could be opened surgically.

MC called PP, who promptly saw the patient and performed an immediate PI, which had little effect. PP then successfully performed cataract surgery, goniosynechialysis, and Kahook dual blade goniotomy, which stabilized the pressures without the need for drops.

MC took over care at the 1-day postoperative period and has been monitoring the patient periodically. Seven years later, IOPs are controlled in the low teens on no medications with stable OCT’s and visual fields. Angle-to-angle anterior-segment OCT shows an open angle with a patent KDB OU with opening to Schlemm’s canal (Figure 2). This case illustrates the efficiency of a collaborative care model with an excellent outcome.

Core Elements of Successful Comanagement

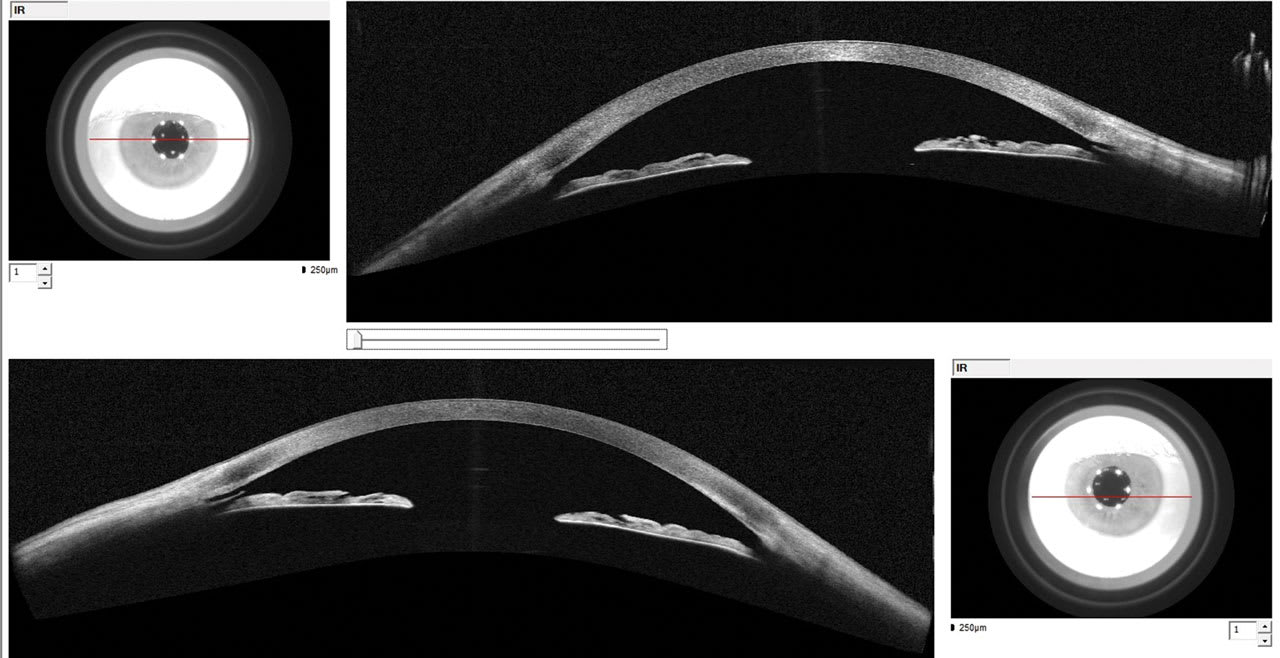

At the heart of successful glaucoma comanagement is seamless communication. Both providers must establish a system for sharing clinical notes, imaging results, visual fields, and treatment plans. Communication should be timely and reciprocal. Optometrists should feel comfortable reaching out with concerns, and ophthalmologists should be responsive and collaborative in their feedback. A referral form (Figure 3) allows optometrists and ophthalmologists to be on the same page. This allows a more efficient use of time reducing the need to inefficiently sift through pages of EMR reports, many of which may be redundant.

Figure 3. Referral form used by the authors at the Glaucoma Institute of State College.

Defined protocols are equally important. Written agreements should outline the division of responsibilities, follow-up intervals, parameters for stability, and thresholds for re-referral. These protocols minimize ambiguity, ensure a consistent standard of care, and provide legal protections for both providers.8

Respect for each professional’s role underpins the comanagement relationship. Recognizing the optometrist’s skill in primary eye care and chronic disease management, alongside the ophthalmologist’s expertise in surgical intervention, creates a foundation of mutual trust. This professional respect not only enhances the quality of collaboration but also reassures patients that they are receiving cohesive, expert care.

A patient-centered focus must remain the guiding principle throughout the comanagement process. Patients should understand who is responsible for each aspect of their care, why shared management is beneficial, and how communication between providers will occur. Transparency fosters confidence and strengthens adherence to treatment and follow-up plans.

Referral Protocols: Optimizing Surgical Outcomes

Successful comanagement demands that optometrists are adept at recognizing when surgical consultation is needed and that ophthalmologists receive thorough and timely referrals.

At any stage of the disease including therapy initiation, SLT should be considered.9,10 We are proponents of SLT as first-line therapy. SLT should also be considered in patients who are noncompliant with topical medications, experience significant side effects, or desire a reduction in medication burden.6 Comprehensive gonioscopic evaluation and patient education about the nature and benefits of laser therapy can smooth the transition to the ophthalmologist’s care if needed.

Similarly, patients with narrow angles identified on gonioscopy or those presenting with angle closure symptoms should be medically stabilized then promptly referred for

YAG PI or cataract/lens replacement surgery.

Cataract patients with mild to moderate glaucoma often benefit from combined cataract surgery with MIGS to optimize intraocular pressure control and visual outcomes.7 Referrals should include detailed histories, medication lists, and the latest imaging and visual field results including progression analysis to assist the surgeon in planning.

For patients with early to moderate open-angle glaucoma requiring surgical intervention, KDB goniotomy presents a minimally invasive option that preserves future surgical potential. Educating patients about these surgical options and collaborating closely with the ophthalmologist at every step strengthens the patient’s experience and clinical outcome. In essence, aligned patient communication with the optometrist and the ophthalmologist promotes patient trust.

Legal and Billing Considerations

Beyond clinical care, providers must navigate legal and billing requirements carefully to avoid regulatory pitfalls. A written transfer-of-care agreement is essential when surgical procedures are involved, clearly specifying who will manage postoperative care and under what circumstances the ophthalmologist will reassume direct patient management.8

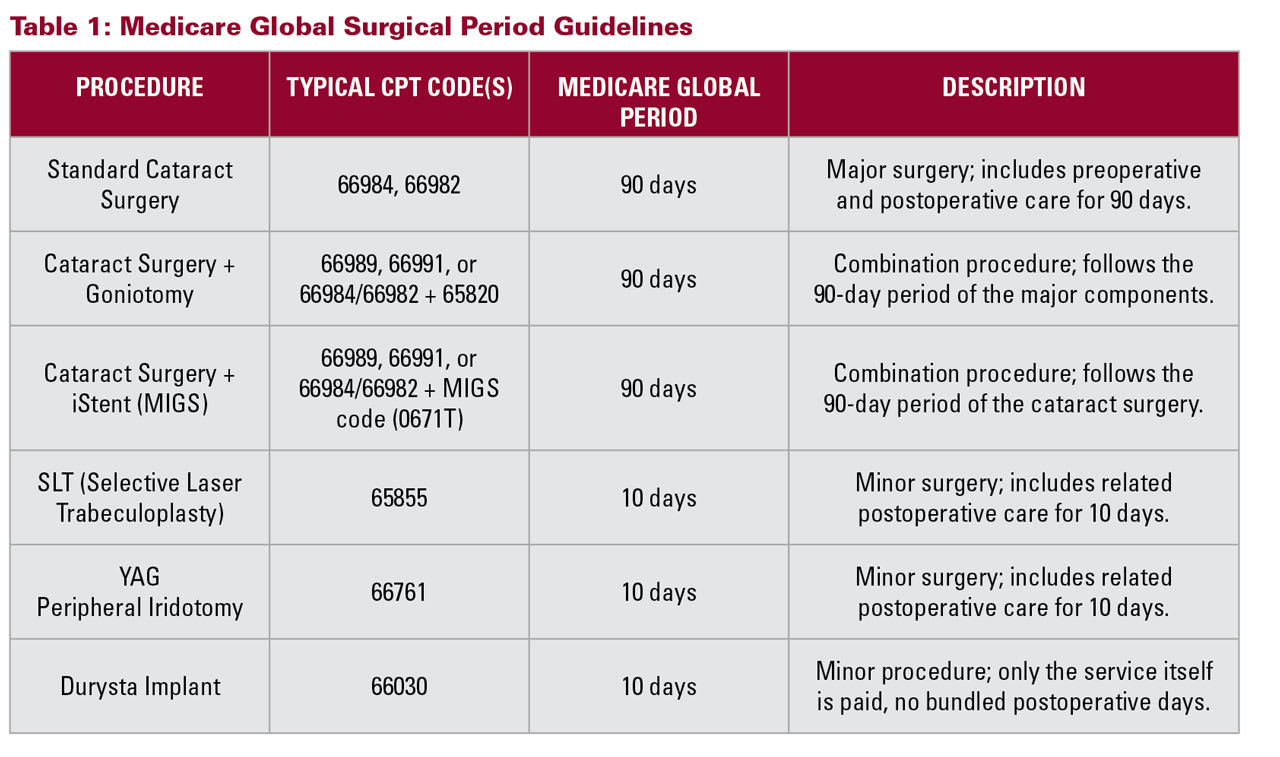

Billing must comply with Medicare’s global surgical period guidelines for postoperative care (Table 1). If care is comanaged, both providers must understand how to split billing functions and ensure that documentation supports the services rendered by each party. Timing of visits, appropriate use of modifiers, and clarity on who is responsible for postoperative follow-up are critical to avoid billing errors or duplicate claims.

Moreover, all comanagement arrangements must strictly adhere to federal laws, including the Stark Law and the Anti-Kickback Statute. These regulations prohibit referrals or financial relationships that could be perceived as incentivized or self-serving. Referrals should always be based solely on clinical need, not on volume-based arrangements or financial benefit. Providers should avoid any agreement that could be construed as an inducement for patient referrals.

Informed consent from the patient is also essential. Patients must clearly understand the roles and responsibilities of each provider and be assured of their right to seamless, uninterrupted care throughout the treatment process.

Maintaining High Standards of Care

High-quality comanagement requires ongoing attention to systems and outcomes. Joint case reviews between optometrists and ophthalmologists can help identify areas for improvement and ensure that patients are receiving optimal care.

Continuing education plays a vital role in keeping both providers at the forefront of glaucoma management. Advances in imaging technology, new medications, and evolving surgical techniques require regular updates to care protocols.

Consistency in testing protocols such as the frequency and method of visual field testing, OCT imaging, and gonioscopy also maintains diagnostic rigor across both settings.

Lastly, patient feedback should be actively sought. Patients’ perspectives on their experience with comanagement can reveal strengths to build on and areas needing refinement.

Conclusion

Glaucoma comanagement between optometrists and ophthalmologists offers a blueprint for patient-centered, efficient, and effective care. By combining the strengths of both professions, this model can meet the growing demand for glaucoma services without sacrificing the quality or personal touch that patients deserve.

Successful comanagement depends on a foundation of clear communication, defined clinical protocols, mutual professional respect, diligent legal and billing practices, and an unwavering focus on the patient. When these elements are in place, the collaborative care model elevates outcomes, empowers providers, and—most importantly—preserves sight for patients living with glaucoma. GP

References

1. Ratnarajan G, Newsom W, Vernon SA, Fenerty C, Harper RA. The effectiveness of a glaucoma shared care service in a hospital setting: a 10-year review. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(1):117–123. doi:10.1038/eye.2014.254

2. Ford BK, Angell B, Liew G, White AJR, Keay LJ. Improving patient access and reducing costs for glaucoma with integrated hospital and community care: a case study from Australia. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19(4):5. doi:10.5334/ijic.4642

3. Ryan B, Jones M, Anderson P, et al. Hospital to community in Wales: what is the value of optometrists playing a greater role in managing neovascular AMD and glaucoma in primary care? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2025;45(1):280-293. doi:10.1111/opo.13397

4. American Optometric Association. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline: care of the patient with primary open angle glaucoma. October 5, 2024. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.aoa.org/a/19461

5. Gedde SJ, Vinod K, Wright MM, et al. Primary open-angle glaucoma preferred practice pattern. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(1):71-150. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.022

6. Samples JR, Singh K, Lin SC, et al. Laser trabeculoplasty for open-angle glaucoma: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(11):2296-2302. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.04.037

7. Kahook MY, Noecker RJ. Complications associated with microinvasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS): a review. Curr Op Ophthalmol. 2016;27(2):99-105.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Global surgery. December 2023. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mln907166-global-surgery-booklet.pdf

9. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1505-1516. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32213-X

10. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Laser in glaucoma and ocular hypertension (LiGHT) trial: six-year results of primary selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2023;130(2):139-151. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.09.009